Riots in Forncett

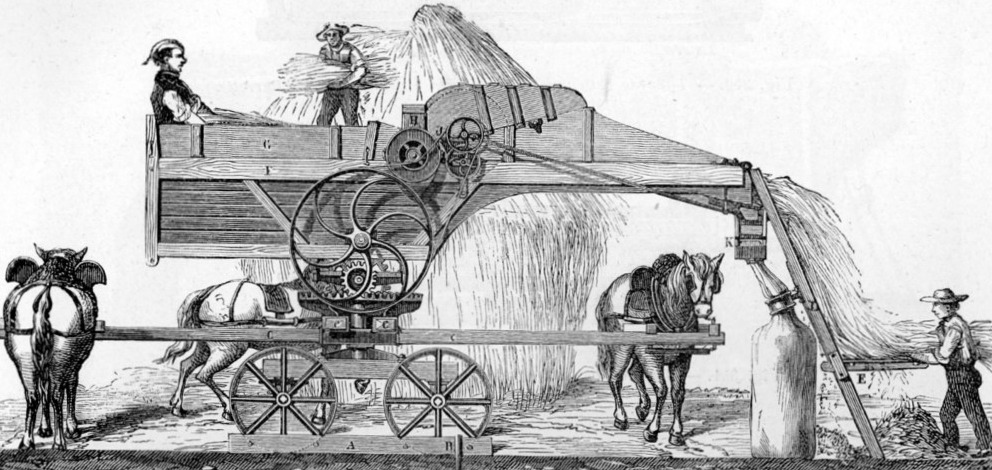

An early horse-powered threshing machine

The Forncett Riots

Background

In the early 1800s, food riots, machine breaking and the protests over tithes, wages and the Poor Laws were all quite common public activities. The overwhelming impression left by acts of incendiarism and riot is one of a periodic, loosely focused spasm of anger against a system that had succeeded in alienating the larger part of its population and had effectively closed all avenues of political, religious and legal expression.

The first horse-powered threshing machine was invented circa 1786 by the Scottish engineer Andrew Meikle. Before such machines were developed, threshing was done by hand with flails: such hand threshing was very laborious and time-consuming, taking about one-quarter of agricultural labour by the 18th century. So the rapid introduction of these machines across East Anglia led to a significant reduction in work for local men.

Another key factor in the outbreaks of unrest was the burden of the church tithe. Originally this had been the church's right to a tenth of the parish harvest. However this had been replaced by a cash levy that was payable to the local Church of England parson and went to pay his (often considerable) stipend. The cash levy was generally rigorously enforced, whether the resident was a Church member or not, and the sum demanded was often far higher than a poor person could afford. Calls for a large reduction in the tithe payment were prominent among the demands of the rioters.

In the summer of 1830 there was a widespread uprising now referred to as the "Swing Riots". The tactics varied from county to county but typically, threatening letters, often signed by "Captain Swing", would be sent to magistrates, parsons, wealthy farmers or Poor Law guardians in the area. The name 'Swing' was apparently a reference to the swinging stick of the flail used in hand threshing.

The Forncett Riots

Riots by local men came to Forncett in 1822 and again in 1830. They were documented in the reminiscences of a local Forncett man, Robert Moore (1794-1874). Robert was the younger brother of William Moore, who was landlord at the Norfolk Arms (the Sope House) from 1813 to 1834. He served as parish clerk in Forncett St Peter for some 33 years and is buried in St. Marys churchyard.

These excerpts are taken from Robert Moore's reminiscences:

1822. The labourers began smashing the machines. Saturday, 2nd March a large group came and pulled me from my breakfast jug of milk and eventually we were as many as 500 gathered at Forncett End. We went to Tacolneston Hall, but Mr. Howes came out with a gun and told them he had no machines, so they went to his brothers at Fundenhall. There they got a threshing machine and dragged it down to Ashwellthorpe Kings Head and broke it to bits and hulled it in a pit. Then they did the same at Hapton to one of Mr. Jack's machines. The Unitarian preacher there came out and spoke to them, but they only hulled him over the hedge. Next day, Sunday, they kept quiet, but Monday and Tuesday they went off to other villages and so there wasn't a machine for ten miles around. Wednesday, the Eye Volunteers came to right side them and took many, to prison. Three went from here and got nine months in Norwich Castle.

The 1822 riots were widespread and many of those involved were apprehended and brought to trial in Norwich. The proceedings were extensively covered in the Norfolk Chronicle of the 16th March 1822.

1830. About this time began the riots against the tithe. I was working for old Mr. Palmer and he came into the barn where I was thrashing and said, "If they come for you, do you go along with them." I asked, "Where?" and he said, "Never mind, only go you along with them." That was on tithe-day. Soon after that some fellows came up to the barn, and one of them ("Capt" Garrod we called him), told me to go along with them. I asked what they were going to do, and he said, "Come out there, don't I flay you alive." He said, "We're going after Parson Jack." When they got into the avenue they were as thick as thick, and they ransacked the house for Mr. Jack, but couldn't find him, do I believe they'd have killed him. Some went up the steeple to look for him but he had gone off first thing in the morning. After a bit Capt. Gwyn the magistrate, Admiral Isby and Mr. Beverley came up. I and another fellow told them we meant no harm to the parson, so they sent us to fetch the church-wardens, but neither of them would come. While we were away the Riot Act was read and when we got back I proposed we should give the rioters a barrel of beer and the people at the Sope House gave us one. While the men were drinking this I said, "Go away and come earlier tomorrow and finish the job." They laughed and made off. Mr. Jack was gone eight weeks. Meantime the farmers met twice at the Sope House to consult, some of them very battlesome, there was a good deal of talk. Then Mr. Jack wrote that if the farmers would heign their labourers wages four pence a week, he would take two shillings off his tithe. They agreed and he came back again, there was another Sope House meeting and he shook hands all round.

This event was reported in the Norfolk Chronicle on 4th

December 1830: